Although clinical pathologists and chemists are experts in the laboratory sciences, they often lack knowledge about the financial infrastructure required for profitable lab services. However, laboratorians who understand the inner workings of the insurance payment system are best positioned to support the lab’s financial health and to protect patients from financial toxicity (1).

In addition, financial knowledge helps lab leaders develop and sustain power in their institution. Too often, laboratorians cede financial power to administrators and consultants who are not knowledgeable about the lab instead of partnering with these other parties as educated and formidable collaborators. At best, this throwing away of financial influence and power leads to underfunding the lab’s clinical mission. At worst, the lab may be shuttered or sold due to the maneuvering that can occur without sufficient lab involvement.

This article outlines five foundational concepts that will benefit laboratorians who currently consider themselves lab economics novices. It is inspired by longer review articles that we published in the recent special edition of The Journal of Applied Laboratory Medicine that was dedicated to lab stewardship (2), as well as an article about insurance company perspectives written by Michael L. Astion, MD, PhD, and Geoffrey S. Baird, MD, PhD (3).

1. The revenue cycle is the system of payment for lab testing

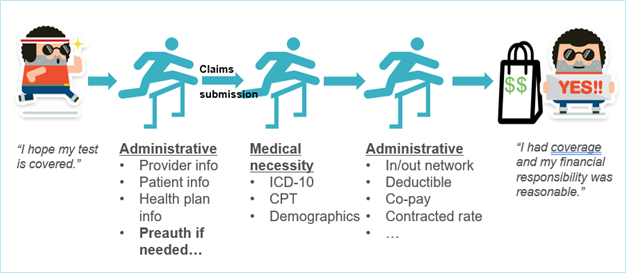

The revenue cycle describes the steps from first patient contact through receipt of payment. But for any single test, the process may be more akin to a road race than to a cycle (Figure 1). The sequence of steps is: 1) patient registration including capture of demographic and insurance information; 2) test order entry; 3) test charge capture; 4) medical coding; 5) submission of a standardized electronic insurance claim that incorporates the aforementioned information; 6) claims adjudication by the payer; 7) management of denials and grievances by the payer, the patient, and the lab; and 8) payment to labs from insurers and patients.

The revenue cycle is easy to understand but seldom easy to navigate. It requires the proper raw materials, information, technology, and relationships. Failure at any point in the cycle can lead to delayed or lost revenue.

Figure 1. A successful race to payment with hurdles representing administrative or medical necessity barriers. The management of denials is not pictured.

Knowledge of the revenue cycle is required to identify where stewardship interventions — such as updating the patient’s insurance plan, promoting the ordering of appropriate tests, or improving coding accuracy — can reduce denials by producing clean claims. Clean claims contain all required administrative and medical data and are therefore usually processed promptly. Like burnt toast, an unclean claim needs thorough scraping to be edible, and even then, it may not be so appetizing.

2. Coding errors are a significant cause of denials

Insurance reimbursement requires accurate coding on standardized forms that have many fields. The two main forms used are CMS-1500 (electronic version = form 837P) and UB-04 (electronic version = form 8371). The primary coding systems in ambulatory medicine are CPT (Current Procedural Technology) codes and ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases) codes.

Each CPT code describes a test or test panel (e.g., CPT 84443 = Thyroid Stimulating Hormone). ICD-10 codes, on the other hand, describe the signs, symptoms, risk factors, and/or underlying diagnoses that represent the clinical indication for testing, i.e., why the test or test panel was ordered. For example, ICD-10 code R63.4 = Abnormal Weight Loss and E05.1 = Thyrotoxicosis with Toxic Single Thyroid Nodule.

Insurance denials are frequently due to mistakes in coding. The most common coding errors are administrative, meaning that information in a particular data field is missing or inaccurate. Another frequent error is coding the claim inadequately to meet a payer’s medical necessity policy (4). One common issue is the use of a nonspecific ICD-10 code (e.g., R53.8 = Other Malaise and Fatigue) when a more specific code in fact applies and would lead to payment (e.g., N18.6 = End-Stage Renal Disease). Understanding which codes commonly lead to denials allows for targeted efforts to improve the accuracy and specificity of procedural and diagnostic coding.

3. Financial toxicity for patients is common, and labs can help reduce it

Patients can face substantial bills related to lab testing, especially when tests are ordered out-of-network and/or when claims are denied by the payer (whether for administrative reasons or for lack of medical necessity). Laboratories also face financial risk from denials: Insurance contracts may prevent or limit billing patients directly, and even when patients can be billed it can be difficult and costly to collect payment.

Ensuring patients are not exposed to surprise bills is a fundamental part of delivering laboratory services. Laboratorians play a role in minimizing patient financial toxicity by supporting stewardship practices that prevent unnecessary or non-reimbursable testing (5). For example, blocking duplicate orders for germline genetic testing that was just performed 6 months ago can save the lab and patient thousands of dollars.

Overall, foundational stewardship interventions that reduce patient financial toxicity include creating and maintaining reasonable test menus; designing decision support tools that promote ordering of appropriate and necessary tests and that reduce ordering of unnecessary tests; and managing send-out testing so that tests are referred to preferred, in-network reference labs.

4. Informatics tools enable smarter financial stewardship

Electronic health records, laboratory information systems, and other health IT systems are key pillars in laboratory financial stewardship. Clinical decision support tools embedded in order entry workflows can help ensure that medical necessity is documented, appropriate diagnostic codes are selected, and critical billing information is captured.

Beyond test utilization, informatics tools can be used to analyze payer behavior. Denial rates can be broken down any number of informative ways (e.g., by CPT code, by payer, by clinical service line). These analyses can be shared with payers to advocate for medical necessity policy changes, or with clinicians whose ordering patterns and documentation practices may be generating avoidable denials.

5. Making friends: Stewardship projects require external collaboration

Laboratorians working on financial aspects of stewardship quickly learn that the meaningful financial data — such as payer fee schedules, denial codes, or claims adjudication patterns — usually reside outside the laboratory. Collaborating with other work units, which includes teams in revenue cycle, IT, and business contracting, is necessary to access and leverage these data.Successful projects also depend on building relationships with clinicians, genetic counselors, and administrative leaders. These partnerships enable labs to deploy interventions that are not only clinically acceptable but also scalable. Lab stewardship work is inherently multidisciplinary and often leads to new professional connections that benefit both the lab and the health system.

Conclusion

For lab leaders to provide optimal clinical services in an integrated health system, they must understand the payment landscape and use this knowledge to gain and sustain power within their system. The foundation is knowing the revenue cycle, from coding best practices to insurance claims processing. Knowledge of claims processing includes both administrative aspects as well as medical necessity determinations. The enablers for harnessing financial knowledge to improve payment are informatics tools and cross-departmental relationships. Understanding the payment system can be a path to increasing profits, reducing financial toxicity to patients, and developing balanced (and not subordinate) relationships with administrators and consultants.

Michael L. Astion, MD, PhD, is director of regional laboratories, director of point-of-care testing, and co-director of reference laboratories in the department of laboratories, Seattle Children’s Hospital and a professor of laboratory medicine and pathology at the University of Washington in Seattle. +Email: [email protected]

Khalda A. Ibrahim, MD, is an assistant clinical professor in the department of pathology and laboratory medicine, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), and a physician informaticist at UCLA Health Information Technology in Los Angeles. +Email: [email protected]

References

- Astion M, Jackson BR. Patient-centered laboratory stewardship can reduce financial toxicity. CLN 2021; https://myadlm.org/cln/articles/2021/october/patient-centered-laboratory-stewardship-can-reduce-financial-toxicity

- Ibrahim KA, Astion ML. Financial analytics for laboratory stewardship: Using data and informatics to increase financial returns for labs and decrease financial harm to patients. J Appl Lab Med 2025; doi: 10.1093/jalm/jfae135.

- Astion ML, Baird GS. Payment matters: Understanding payer perspectives on laboratory stewardship. J Appl Lab Med 2025; doi: 10.1093/jalm/jfae129.

- Astion M. Medical necessity policies: Creating opportunities for better test utilization and fair payment. CLN 2023; https://myadlm.org/cln/articles/2023/julaug/medical-necessity-policies-creating-opportunities-for-better-test-utilization-and-fair-payment

- Astion M, Jackson BR. Patient-centered laboratory stewardship can reduce financial toxicity. CLN 2021; https://myadlm.org/cln/articles/2021/october/patient-centered-laboratory-stewardship-can-reduce-financial-toxicity