Healthcare professionals’ knowledge of genetics and available testing options is expanding rapidly, leading to more informed diagnoses, better care management, and targeted therapies. In spite of this, the complexities of genetic risk assessment and test selection, coupled with the abundance of tests on the market, also have made genetic testing a common tool for healthcare fraud.

Fraud, waste, and abuse (FWA) are a spectrum of behaviors that result in unnecessary costs. Examples include duplicate ordering or billing, billing for services not rendered or performed, and “unbundling” claims to bill for each test separately instead of billing for the relevant panel. In particular, fraud involves intentional deception for personal or financial gain and often includes criminal activity. A behavior could be deemed fraud, waste, or abuse depending on the intent and context.

The costs of fraudulent activity in the healthcare sector are wide-ranging. Financially, fraud alone is estimated to comprise 3%−10% of the national healthcare expenditure (NHE) in the United States — potentially 1 out of every 10 dollars (1). The majority of NHE is funded by the federal government, which means taxpayer money is forfeited. Fraudulent claims cause monetary strain for public and private insurance companies (payors). In turn, measures to address fraud, such as prior authorizations, audits, and fraud prevention programs, may add to the administrative burden and systemic complexities in healthcare. People may experience unexpected bills for goods or services they never received, or pay increased premiums as payors balance their budgets. Fraud can cause future harm if a medically necessary claim is denied because the insurance company thinks it has previously been provided through a false claim.

Federal and state governments, as well as various coalitions, have implemented legislation and task forces to help with the identification, prevention, and prosecution of healthcare fraud. Legislation such as the Federal Civil False Claims Act (FCA), the Anti-Kickback Statute, the Physician Self-Referral Law (Stark Law), and the Criminal Health Care Fraud Statute serves as the primary mechanism for federal prosecution. Federal organizations, including the Department of Justice and the Office of the Inspector General, have highlighted genetic testing specifically as a common area of fraudulent activity. Perhaps most famously, in 2019’s Operation Double Helix, federal law enforcement charged 35 individuals responsible for over $2.1 billion in losses through submission of fraudulent cancer genetic testing (2).

Given the high prevalence and costly nature of genetic testing fraud, we set out to better understand it in order to inform preventive strategies. We did this by performing a qualitative analysis of 42 court cases involving genetic testing fraud published between 2019 and 2023 through a retrospective review of a legal database and public sources (3).

Themes and common characteristics of genetic testing fraud

Six primary themes emerged from our analysis:

- Submission of medically unnecessary claims: The majority of cases reported that genetic testing claims were medically unnecessary. In many cases, testing was completely unrelated to patients’ true medical histories or diagnoses.

- Payment for signed orders: In 90% of cases, healthcare providers received kickbacks or bribes to sign orders for genetic testing, often for patients they never met. These payments were disguised as processing and handling fees for testing, research incentives, investment opportunities, and meals and happy hours.

- Minimal or no patient contact: In 71% of cases, providers had minimal or no contact with the patients for whom they ordered genetic tests. Intermediaries such as “telemarketing” companies often identified lists of beneficiaries, arranged logistics of sample collection, secured signed genetic test orders, and submitted for reimbursement.

- Inappropriate billing practices: More than half of the analyzed cases revealed improper billing practices, including charging for services not rendered and “upcoding,” in which a less accurate or inaccurate procedural code is selected to maximize reimbursement.

- Fraud concealment: Perpetrators employed various strategies, including wire fraud and money laundering, to hide their profits. Sham contracts masked illegal payments as legitimate marketing services for laboratories or research initiatives for providers.

- Inappropriate documentation: Nearly half of the cases involved fraudulent documentation, such as falsifying patient records, misrepresenting diagnoses, or fabricating signatures. Fraudulent documentation supported false claims and legitimized medically unnecessary testing so claims would be reimbursed.

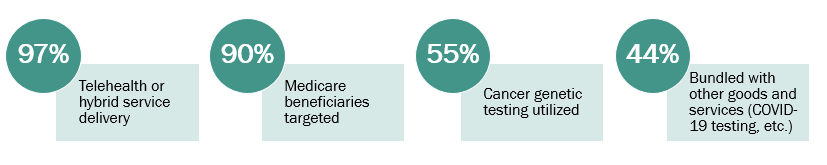

We also reviewed characteristics of claims submitted fraudulently to identify categories of genetic testing claims that could be prioritized in fraud identification and management policies (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cases involving telehealth, targeting Medicare beneficiaries, and utilizing cancer genetic testing were three of the most common categories of fraud we identified. These are illustrated by a striking case that involved a doctor who “received approximately $30 in exchange for each doctor’s order he signed authorizing [durable medical equipment (DME)] and cancer genetic test orders that were not legitimately prescribed, not needed, or not used — totaling more than $466,000 in kickbacks. The Medicare beneficiaries for whom [doctor] prescribed DME and cancer genetic testing were targeted by telemarketing campaigns and at health fairs and were induced to submit to the cancer genetic testing and to receive the DME regardless of medical necessity” (4).

Another of the court cases we analyzed that illustrates a number of the themes above involved a nurse practitioner who, in 2020, “ordered more cancer genetic tests for Medicare beneficiaries than any other provider in the nation, including oncologists and geneticists. She then billed Medicare as though she were conducting complex office visits with these patients, and routinely billed more than 24 hours of ‘office visits’ in a single day” (5).

The role of genetics experts

As the majority of cases reported medically unnecessary testing, integrating genetics experts like genetic counselors and medical geneticists into the ordering and billing process is essential to combatting genetic testing FWA. Because of the complexity of genetics and genetic testing, high levels of training are needed to perform risk assessments and select the best test options. Similarly, genetics experts informed about FWA are the perfect reviewers (or whistleblowers) to recognize when a genetic test does not quite make sense with a patient’s given medical history.

Importantly, integration of genetics expertise must be balanced with accessibility. Increased access to genetics providers at the ordering or claim review stages may help prevent and uncover fraudulent activity. Efforts that may increase access include genetic counseling licensure and recognition by Medicare. Laboratory stewardship and insurance claim review programs also aim to ensure best testing practices and limit waste for medically necessary testing.

Other steps we can take to prevent FWA

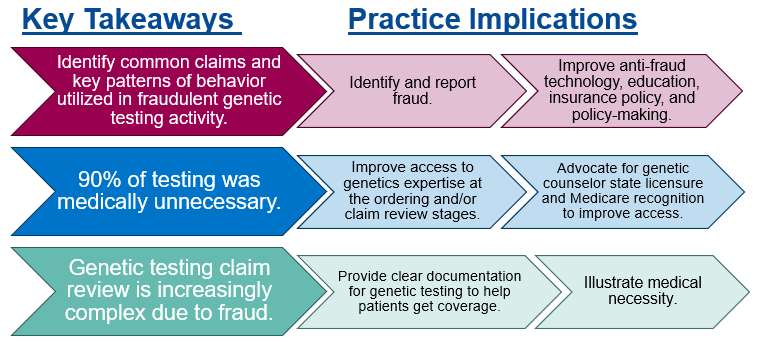

Although our findings focused on genetic testing fraud, which is intentional, medically unnecessary testing, inaccurate billing, and inappropriate documentation practices can occur unintentionally as well. Either way, if you witness suspicious activity, report it to 1-800-HHS-TIPS or oig.hhs.gov/fraud/hotline. Additionally, certain key takeaways can be used to examine and modify practices within our own organizations that may fall on the waste and abuse end of the spectrum (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Fraud trends can inform policy and anti-fraud technology, including data analytics or artificial intelligence, which in turn can supplement genetics expertise and traditional methods of audits or prior authorization. Broad public education initiatives, as well as targeted education for populations like Medicare beneficiaries, laboratory stewardship programs, and payors, may also help prevent and identify FWA.

Conclusion

FWA using genetic testing causes significant harm to individuals, laboratories, payors, and the healthcare system overall. Continuing to research trends can aid policies and education in reducing FWA while supporting the genuine needs of patients. Through laboratory stewardship and individual accountability, we can better safeguard patients and the genetics field by identifying and reporting fraud, raising awareness of FWA, and reflecting on personal and institutional practices with the goal of optimizing our healthcare resources.

Rachel Notestine, MS, CGC, is a public health genetics consultant with the Ohio Department of Health in Columbus. +EMAIL: [email protected]

Read the full September-October issue of CLN here.

References

- The challenge of health care fraud. National Health Care Anti-Fraud Association. https://www.nhcaa.org/tools-insights/about-health-care-fraud/the-challenge-of-health-care-fraud/ (Accessed July 7, 2025).

- U.S. Department of Justice. Federal law enforcement action involving fraudulent genetic testing results in charges against 35 individuals responsible for over $2.1 billion in losses in one of the largest health care fraud schemes ever charged. https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/federal-law-enforcement-action-involving-fraudulent-genetic-testing-results-charges-against (Accessed March 31, 2024).

- Notestine R, Singletary CN, Choates M, et al. Fraud in genetic testing: Swindling the system. Genet Med 2025; doi:10.1016/j.gim.2024.101248.

- U.S. Department of Justice. Doctor pleads guilty to role in $54 million Medicare fraud scheme. https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/doctor-pleads-guilty-role-54-million-medicare-fraud-scheme (Accessed February 25, 2024).

- U.S. Department of Justice. Nurse practitioner convicted of $200 million health care fraud scheme. https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/nurse-practitioner-convicted-200m-health-care-fraud-scheme (Accessed March 28, 2024).