For decades, cervical cytology has been the mainstay of cervical cancer screening, but emerging evidence about the pathologic role of human papillomavirus (HPV) in cervical cancer is changing the screening landscape for this disease. As the science involving HPV advances and as guidelines from professional organizations evolve, laboratorians need to keep abreast of cervical cancer testing developments and work with clinicians to ensure appropriate test utilization.

Cervical Cytology

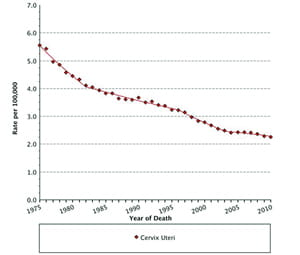

Widespread introduction of cervical cytology or Papanicolaou (Pap) testing in the United States during the 1950s and 1960s launched a trend of markedly reduced squamous cell cervical cancer-related mortality. Cervical cancer, once the most frequent cause of cancer death in women, now ranks 14th among cancer deaths in the U.S. (See Figure 1, p. 9) (1). Cytology-based screening aims to detect squamous cell cancers, which account for about 80% of cervical cancer. It is less useful for detecting adenocarcinomas arising from endocervical glands because these cells are less evident than ectocervix squamous cells by this method. Fortuitously, evidence shows that HPV testing is more effective than cervical cytology in detecting both adenocarcinoma and glandular cell cancers of the cervix, thereby making it a useful adjunct to cervical cytology (2).

Age-Adjusted U.S. Mortality Rates By Cancer Site

All Ages, All Races, Female, 1975-2012

Mortality source: US Mortality Files, National Center for Health Statistics, CDC.

Rates are per 100,000 and are age-adjusted to the 2000 US Std

Population (19 age groups – Census P25-1130). Regression lines

are calculated using the Joinpoint Regression Program Version 4.0.3,

April 2013, National Cancer Institute

HPV Testing

HPV is a common, sexually transmitted DNA virus comprised of more than 100 genotypes. In the late 1970s, Dr. Harald zur Hausen first described HPV's role in the development of cervical cancer (3). Significant evidence now exists to support a causal relationship between duration of infection with a high risk HPV genotype (HR-HPV) and development of cervical cancer (4). Early HPV infections can be recognized most often by cytology as low grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LGSIL) or by histology as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1 (CIN 1) (5). Most such infections spontaneously resolve by host immunity, and their corresponding cellular abnormalities revert to normal.

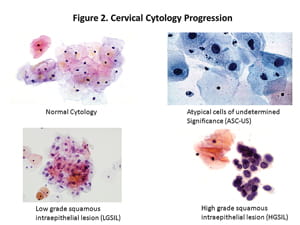

Because HR-HPV infections are very common in young women and most women clear HPV infections within 6–12 months, the presence of HPV DNA alone does not guarantee that cervical dysplasia or cervical cancer is present or will develop in women younger than age 30. When HR-HPV infections persist, cervical pre-cancers, such as high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HGSIL) by cytology or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or 3 (CIN 2 or 3) by histology, can arise from genetic instability and clonal expansion of highly transformed cells. Later stage lesions like these are much less likely to regress (See Figure 2, p. 10). Factors leading to HPV persistence include: HPV genotype—with the greatest risk from HPV 16 and 18—increasing age, smoking, mutagens, immunosuppression, inflammation, hormones, and genetic factors. This and other evidence demonstrates that HPV testing could play an important role in cervical cancer screening.

Cervical Cytology Progression

In 1997, Digene received Food and Drug Administration (FDA) clearance for the Hybrid Capture HPV DNA assay as an aid in triaging women with equivocal cervical cytology. Six years later the FDA cleared Digene's Hybrid Capture 2 DNA assay (HC2) as an adjunctive screen with cervical cytology for women 30 years and older. At this point, the field of HPV test interpretation became confounded as some clinical laboratories developed real-time polymerase chain reaction tests with better analytic sensitivity than HC2 which, unfortunately, did not translate into improved prediction of cervical cancer. Many studies demonstrated that clinical cut-offs for HPV viral loads were necessary to establish levels that better predicted cervical cancer risk(6–8). Given these circumstances, HC2, as the only FDA-cleared HPV assay, served as the gold standard for cervical cancer screening until 2011 and 2012 when the FDA approved the Aptima, Cervista, and Roche HPV assays (9).

Current HPV assays differ in methodology, target, and analytic cutoffs, but are all interpreted as positive or negative for HR-HPV and carry equivalent clinical implications for most practitioners. As these newer methods are adopted more broadly, we will likely see more studies demonstrating performance characteristic differences among them. For example, a large number of studies have already demonstrated that the Aptima HPV assay has equivalent sensitivity but superior specificity to HC2 in two testing situations. The first involves reflex testing, in which cytology testing revealed atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US). The second concerns co-testing via cytology and HPV testing in women older than age 30 to detect ≤CIN 2 likely to indicate persistent infection and clinically significant cervical dysplasia (10–13).

This improved specificity translates into fewer false positive screening results, saving patients undue anxiety and unnecessary follow-up diagnostic procedures. Differences in the HPV target between the two assays might contribute to their different specificities. E6 and E7 mRNA, the targets of the Aptima method, are believed to be expressed at higher levels during persistent infections, while HPV DNA levels, the target of HC2, are high early in the course of HPV infection. Evidence also suggests the potential for false-negative HPV results from assays that target the L1 region of the HPV genome, since portions of this region have been shown to be lost on viral integration during persistent infections (14). A recent expert opinion paper by Tjalma and Depuydt promotes the use of an E6/E7-based assay over an L1-based method for just such reasons (15). Thus, based on assay-specific performance characteristics, we may expect to see distinct indications and outcomes put forward for each test method.

Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines

2015 will mark the 40th anniversary of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) having first published a technical bulletin as guidance for Pap testing (16). Screening guidelines have continually evolved since then, with various professional organizations often offering differing recommendations. By 2012 it seemed that everyone—at least in the U.S.—had come to agreement, as the American Cancer Society (ACS), American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP), and American Society for Clinical Pathology (ASCP) published joint consensus guidelines for the Prevention and Early Detection of Cervical Cancer (17), followed by ACOG, which later that year released new guidelines for cervical cancer screening (See Table, p. 10) (18). These guidelines are primarily in agreement with the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force's (USPSTF) current recommendations for cervical cancer screening (19). A major development among these guidelines is that women ages 30–65 who undergo co-testing with HPV and cytology need retesting only every 5 years. These recommendations are for screening only and do not relate to other uses of cytology and HPV testing such as follow-up of patients with untreated disease, post-colposcopic, or immediate post-treatment follow-up or surveillance. These are all circumstances in which testing at more frequent intervals might be appropriate.

| Summary of 2012 ACOG, ASCP, ACS, and ASCCP Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines for Women of Average Risk |

||

|---|---|---|

| Age | Screening Recommendation | Comments |

| Less than 21 years |

No cervical cancer screening of any kind | HPV testing should not be used for screening or ASC-US reflex in this age group. |

| 21 - 29 years | Cytology alone primary screening every 3 years (acceptable) HPV testing with cytology ASC-US findings (preferred) |

Routine HPV co-testing is not recommended in this age group. HPV testing is recommended in cases of ASC-US cytology. |

| 30 - 65 years | HPV and cytology 'co-testing every 5 years (preferred) Cytology alone every 3 years (acceptable) |

Screening by HPV testing alone is not recommended for most clinical settings. |

| Over 65 years | No screening following adequate history of negative prior screening | Women with history of >CIN 2 should continue screening for at least 20 years. |

| After hysterectomy | No screening if no previous history of >CIN 2 | Continue screening (cytology) if there is history of >CIN 2 in the past 20 years or cervical cancer ever. |

| A more complete summary of these recommendations is available at http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/cervical/pdf/guidelines.pdf | ||

In general, the new guidelines extend the recommended screening intervals to every 3 years for women 21–29 years undergoing cytology alone, or every 5 years for those ages 30–65 who undergo both cytology and HPV testing. There is significant evidence that the use of co-testing in the latter group allows for an extended test interval and provides better sensitivity for >CIN 3 than screening by cytology alone (20–22). The guidelines do not recommend co-testing in women 21–29 years because of the high prevalence of HPV in this age group; however, HPV testing can be useful for these patients if the cytology results identify ASC-US findings.

Screening more frequently than these recommendations not only offers no benefit but has significant risks. Both the USPSTF and ACS/ASCCP/ASCP documents state that screening more often than every 3 years causes significant harm in terms of potential short-term psychological stress, additional procedures, and assessment and treatment of transient lesions, vaginal bleeding and infection, and potential adverse pregnancy outcomes.

The new guidelines also advise no longer screening women older than age 65 if they have a documented negative screening history. The documents define adequate negative screening results as three consecutive negative cytology results or two consecutive negative co-test results within the past 10 years, with the most recent test performed within 5 years. Women with a history of ≥CIN 2 or adenocarcinoma in situ should continue screening for 20 years after spontaneous regression or appropriate management even if it extends the screening past age 65 years.

Future evidence may show that less frequent screening is appropriate for women who have received the HPV vaccine, but given the limitations of current research and the low vaccination coverage among U.S. adolescents prior to first intercourse, the screening protocol is now the same for both vaccinated and unvaccinated women.

HPV Genotyping

The major guidelines published in 2012 also introduced an emerging role for definitively identifying HPV genotypes 16 and 18, specifically in women who have discordant co-testing results with normal cytology and a positive HR-HPV result. These women can be managed by either repeat co-testing in 1 year or immediate HPV16/18 genotyping. If HPV genotyping reveals the presence of HPV 16 or 18, the patient would undergo colposcopy but if this result is negative she would undergo repeat co-testing in 1 year. The major guidelines do not denote a preference between immediate HPV genotyping and 1 year co-testing follow-up. They do specify, however, that women should not be tested for genotypes other than 16 and 18. Of note, since the guidelines were published in 2012, the FDA approved the Aptima HPV 16 18/45 Genotype Assay as a follow-up to positive HR-HPV results in ASC-US reflex and co-testing indications. Despite the guidelines' recommendations, we have seen slow adoption of HPV genotyping requests by providers at our institution thus far.

HPV as Primary Screening

The role of HPV testing in cervical cancer screening is continuing to evolve. Many studies have considered the possibility of HPV testing superseding cytology as a primary screen for cervical cancer (23–25), and there are strong proponents on each side of this debate (26, 27). A central point in this issue is the superior negative predictability of HPV tests over cervical cytology. Most recently, Ronco et al. evaluated data from four randomized controlled studies in Europe and found that HPV screening appears to offer 60–70% greater protection against invasive cervical cancer than cytology (28). In July 2013, Roche submitted a premarket approval supplement to the FDA seeking the addition of a cervical cancer primary screening indication for the company's cobas HPV test. The filing is based on evidence coming from 3-year follow-up data of the 47,000 women included in the Roche-sponsored ATHENA study (29). On March 12, FDA held a public meeting of the Microbiology Devices Panel of the Medical Devices Advisory Committee and the committee voted unanimously that the data was sufficient to prove safety and effectiveness for the Cobas HPV test for primary screening (30). FDA is not bound to abide by committee recommendations, but usually does. When an FDA-approved HPV test for primary screening becomes available in the U.S., its adoption in clinical practice certainly would lag until major guidelines endorse such a strategy and clinicians recognize its utility.

Conclusion

Debate over the best utilization of cytology and HPV testing in cervical cancer will no doubt intensify and continue for some time. It is critical that laboratorians are familiar with these methods and the evidence supporting their utility. We must inform clinicians and champion appropriate test utilization for patient care. This quote by Britain's 19th century prime minister, Benjamin Disraeli, certainly applies to cervical cancer screening: "Change is inevitable. Change is constant."

REFERENCES:

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, and Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2012;

62:10–29. - Guidos BJ and Selvaggi SM. Detection of endometrial adenocarcinoma with the ThinPrep

Pap test. Diagn Cytopathol 2000;23:260–5. - Dürst M, Gissmann L, Ikenberg H, et al. A papillomavirus DNA from a cervical carcinoma

and its prevalence in cancer biopsy samples from different geographic regions. Proc Natl Acad

Sci USA 1983;80:3812–5. - Tota JE, Chevarie-Davis M, Richardson LA, et al. Epidemiology and burden of HPV infection

and related diseases: Implications for prevention strategies. Prev Med 2011;53 Suppl 1:S12–21. - Wheeler CM. Natural history of human papillomavirus infections, cytologic, and histologic

abnormalities, and cancer. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2008;35:519–36. - Gravitt PE, Burk RD, Lorincz A, et al. A comparison between real-time polymerase chain

reaction and hybrid capture 2 for human papillomavirus DNA quantitation. Cancer Epidemiol

Biomarkers Prev 2003;12:477–84. - Schiffman M, Wheeler CM, Dasgupta A, et al. A comparison of a prototype PCR assay

and hybrid capture 2 for detection of carcinogenic human papillomavirus DNA in women with

equivocal or mildly abnormal papanicolaou smears. Am J Clin Pathol 2005;124:722–32. - Kulasingam SL, Hughes JP, Kiviat NB, et al. Evaluation of human papillomavirus testing

in primary screening for cervical abnormalities: Comparison of sensitivity, specificity, and

frequency of referral. JAMA 2002;288:1749–57. - Food and Drug Administration. Nucleic acid based tests. www.fda.gov/

MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/InVitroDiagnostics/ucm330711.htm

(Accessed February 24, 2014). - Stoler MH, Wright TC Jr, Cuzick J, et al. APTIMA HPV assay performance in

women with atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance cytology results. Am

J Obstet Gynecol 2013;208:144.e1–8. - Arbyn M, Roelens J, Cuschieri K, et al. The APTIMA HPV assay versus the hybrid

capture 2 test in triage of women with ASC-US or LSIL cervical cytology: A meta-analysis

of the diagnostic accuracy. Int J Cancer 2013;132:101–8. - Ratnam S, Coutlee F, Fontaine D, et al. Aptima HPV E6/E7 mRNA test is as sensitive

as hybrid capture 2 assay but more specific at detecting cervical precancer and cancer.

J Clin Microbiol 2011;49:557–64. - Clad A, Reuschenbach M, Weinschenk J, et al. Performance of the Aptima high-risk

human papillomavirus mRNA assay in a referral population in comparison with hybrid capture

2 and cytology. J Clin Microbiol 2011;49:1071–6. - Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary

cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol 1999;189:12–9. - Tjalma WA and Depuydt CE. Cervical cancer screening: Which HPV test should be used

—L1 or E6/E7? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2013;170:45–6. - American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Technical Bulletin Number 29:

The frequency with which a cervical-vaginal cytology examination should be performed in

gynecologic practice. 1975. - Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al. American Cancer Society, American Society for

Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening

guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer.

CA Cancer J Clin 2012;137:516–42. - Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 131: Screening

for cervical cancer. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:1222–38. - Moyer VA. Screening for cervical cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force

recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:880–91. - Dillner J, Rebolj M, Birembaut P, et al. Long term predictive values of cytology and

human papillomavirus testing in cervical cancer screening: Joint European cohort study.

BMJ 2008;337. - Katki HA, Kinney WK, Fetterman B, et al. Cervical cancer risk for women undergoing

concurrent testing for human papillomavirus and cervical cytology: A population-based study

in routine clinical practice. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:663–72. - Rijkaart DC, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, et al. Human papillomavirus testing for the

detection of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer: Final results of the

POBASCAM randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:78–88. - Cuzick J, Clavel C, Petry KU, et al. Overview of the European and North American

studies on HPV testing in primary cervical cancer screening.

Int J Cancer 2006;119:1095–101. - Ogilvie GS, Krajden M, van Niekerk DJ, et al. Primary cervical cancer screening with

HPV testing compared with liquid-based cytology: Results of round 1 of a randomised

controlled trial - the HPV FOCAL Study. Br J Cancer 2012;107:1917–24. - Luyten A, Scherbring S, Reinecke-Luthge A, et al. Risk-adapted primary HPV

cervical cancer screening project in Wolfsburg, Germany – Experience over 3 years.

J Clin Virol 2009;46 Suppl 3:S5–10. - Isidean SD and Franco EL. Embracing a new era in cervical cancer screening.

Lancet 383:493–4. - Whitlock EP, Vesco KK, Eder M, et al. Liquid-based cytology and human

papillomavirus testing to screen for cervical cancer: A systematic review for the

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:687–97. - Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfstrom KM, et al. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for

prevention of invasive cervical cancer: Follow-up of four European randomised

controlled trials. Lancet 2014;383:524–32. - Wright TC Jr, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, et al. The ATHENA human

papillomavirus study: Design, methods, and baseline results.

Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;206:46.e1–11. - Food and Drug Administration. Microbiology devices panel of the medical

devices advisory committee meeting materials 2014. www.fda.gov/Advisory

Committees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/MedicalDevices/MedicalDevices

AdvisoryCommittee/MicrobiologyDevicesPanel/ucm388531.htm

(Accessed March 12, 2014).