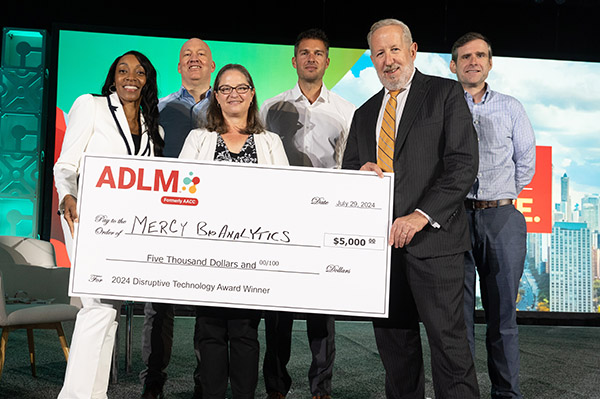

A blood-based test from Mercy BioAnalytics that has the potential to become the first FDA-approved test for ovarian cancer screening won ADLM’s 2024 Disruptive Technology Award, presented at ADLM 2024 in Chicago. The honor recognizes innovative testing solutions that improve patient care.

“We were so thrilled,” said Dawn Mattoon, PhD, chief executive officer of the company, based in Waltham, Massachusetts “It was unexpected. We applied thinking we were maybe a step too early. We know how much more work we have to do.”

Most blood tests in development for early detection of cancers rely on identifying and measuring circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) — genetic material shed from tumor cells. But that has limitations, Mattoon said. For one, ctDNA is released into circulation only when cells die. In the early stages of cancer, a tumor mass is very small, and its cells are busy dividing and growing without a lot of cell death occurring.

Mercy’s test, called Mercy Halo, instead analyzes extracellular vesicles (EVs) — small, membrane-bound particles shed continuously by all cells, which are abundant in circulation. For example, 1 mL of blood from a stage I cancer patient with a 1 cm tumor contains 100,000 tumor-derived EVs, according to company materials. The same sample may contain at most one copy of ctDNA.

The Mercy Halo assay is designed to detect multiple cancer-related biomarkers on the EVs’ surfaces. When EVs are shed from tumor cells, they carry genomic and proteomic markers derived from their cell of origin, Mattoon explained. “Think of that kind of like a sphere, decorated on the outside with biomarkers.”

How the Mercy Halo test works

The Mercy Halo assay introduces a magnetic bead coated with a capture antibody directed toward specific biomarkers decorating the EV surface. It pulls EVs with these biomarkers out of the sample for study. However, some of them may be healthy, noncancerous cells, Mattoon said. Then, to gain additional sensitivity and specificity, the test introduces two additional antibodies, directed against two additional biomarkers on the same EV, now sitting captured on the magnetic bead. Each detection antibody is conjugated to a double-stranded oligonucleotide with complementary, single-stranded overhangs.

“When, and only when, they bind in close proximity to one another on the surface of that captured EV will those two oligos anneal,” Mattoon said. “We do a ligation step, and that forms a template for PCR” that can be read on any qPCR instrument. “It’s really through the selection of those three biomarkers that we’re able to drive sensitivity and specificity for, in this case, early-stage ovarian cancer.” The biomarker names are proprietary, she said.

The FDA in May granted the company Breakthrough Device Designation for the screening test in asymptomatic, postmenopausal women, and company staff are now working with the FDA on a pivotal study design, Mattoon said. “We want to make sure that we have really strong alignment with the FDA before we move into the pivotal study,” she said. “It is absolutely our intention to submit this to FDA for approval, and we hope to do that in 2026.”

There currently is no screening test for asymptomatic women to detect ovarian cancer, of which some 20,000 new cases are reported a year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More than 70% of ovarian cancers are diagnosed in women over age 50, and nearly 80% are diagnosed at an advanced stage of disease.

For women at high risk of developing ovarian cancer because they have a family history or a mutation in the BRCA gene, “the best we can do for them right now is recommend that they have their ovaries and fallopian tubes surgically resected,” Mattoon said. “For the rest of us who don’t have any of those risk factors, we basically just have to hope that we don’t get ovarian cancer. There is no screening modality. That’s what we are endeavoring to do.”

From inspiration to clinical evidence

The original technology was the brainchild of Joseph Sedlak, an MD/PhD candidate at Harvard University with his own unique story. As an undergraduate at the University of Michigan, Sedlak was part of a dedicated program, the Blavin Scholars, for young adults who had spent time in foster care or were navigating education without support from parents or guardians. The program, started by financier and philanthropist Paul Blavin, provides mentors and other wraparound services. With Blavin’s support, Sedlak graduated summa cum laude and entered an MD/PhD program at Harvard and MIT, along the way becoming Blavin’s adopted son.

It was during this graduate work that Sedlak identified early detection as an area of significant unmet need to reduce cancer morbidity and mortality. Together, Sedlak and Blavin founded Mercy BioAnalytics in 2018 based on Sedlak’s novel idea to leverage EVs in early cancer detection.

Because EVs are so abundant, the Mercy Halo test can detect them even in very small sample volumes, Mattoon said. For the ovarian cancer test in development, only 300 μL are needed. That enables the test to be run on material stored in biorepositories from previous clinical trials or research studies.

Recently, the company partnered with investigators from University College London to run the test on a retrospective of baseline blood samples from postmenopausal participants from the United Kingdom Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS). During that trial, participants were randomized to receive no screening, annual multimodal screening including serum measures of the biomarker CA125, or annual transvaginal screening. The study found a significant (10%) decrease in late-stage, high-grade serous ovarian cancer but no decrease in deaths from these screening options.

In the new study with Mercy BioAnalytics, among samples from over 1,300 women, investigators found that the Mercy Halo test was able to detect high-grade serous ovarian cancer up to 3 years prior to diagnosis. The sensitivity 0−12 months prior to diagnosis was 82% (and 85% for stages I and II), compared with 63% (46% for stages I and II) for CA125 at a cut-off of 15.5 U/mL established in an independent study. The specificity, in controls, of the EV-based blood test was 97.7% and of CA125 was 95.5%

“That blows the doors off CA125,” Mattoon said. “It’s really the most significant advancement in ovarian cancer early detection in 40 years.” These results were presented in a poster in June at the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s annual meeting.

In additional study findings, the AUC 0–12 months prior to diagnosis was 0.94 (0.98 for stages I and II) compared with 0.87 (0.80 stages I and II) for CA125. And, in samples from women who had a false positive transvaginal ultrasound who underwent trial surgery during the initial study and had benign pathology, Mercy Halo’s specificity was 97.6%, compared with 89.5% for CA125.

The technology also could be suitable as an aid to diagnosis for a woman presenting with symptoms of ovarian cancer, Mattoon said. Ovarian cancer typically presents with nonspecific symptoms such as diffuse pelvic pain or a feeling of fullness. Combined with a lack of a screening test, she said, “Women are almost always diagnosed at an advanced stage of disease, and their outcomes are terrible. Most of these women, unfortunately, will succumb to their disease.” If ovarian cancer is detected early, at a localized stage, she said, more than 90% of women will survive for 10 years.

The biomarkers targeted by Mercy Halo may be generalizable to other cancers, Mattoon said. The company is working on another indication, for early detection of lung cancer in individuals who are at high risk because of their smoking history. They also have feasibility data for breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers, she said.

It’s pretty easy for companies to do case-control studies that include some people already diagnosed with a condition and some who are healthy, and many emerging technologies can discriminate postdiagnostic cases from healthy controls, Mattoon said. Where some start to falter is in translating early performance into asymptomatic individuals. But Mercy validated the performance of their test in the intended use population in their study with University College London, which makes Mattoon optimistic about their upcoming pivotal validation study.

“It’s an amazing time to be in the space,” she said. “I believe that blood-based cancer screening will come into the norm of clinical practice over the next decade. Who wouldn’t want to be a part of that?”

The two other finalists for the award were Dionysus Digital Health for its Enlighten Test, an epigenetic test taken during pregnancy that predicts future risk of postpartum depression, and Vitestro, for its Vitestro autonomous blood-drawing device.

The Enlighten Test scans epigenetic biomarkers from a blood test during pregnancy, specifically looking at methylation status of two genes: TTC9B and HP1BP3. TTC9B is associated with estrogen activity while HP1BP3 mediates anxiety. Pregnant people can then share results with their physicians and discuss screening for postpartum depression after the baby is born.

The Vitestro device combines artificial intelligence-based, ultrasound-guided imaging with robotic needle insertion to ensure accurate, secure blood collection. The procedure — from tourniquet to bandage application — is performed automatically.

Karen Blum is a freelance medical/science writer in Owings Mills, Maryland.

+Email: [email protected].