Carbon dioxide (CO2) is a byproduct of several human metabolic processes, most notably the Citric Acid (Krebs) Cycle, which produces two molecules of CO2 per cycle. The fate of metabolically produced CO2 is determined partly by chemistry and partly by respiration. Three measures are used clinically to assess CO2 status: total CO2, partial pressure of CO2 gas (pCO2), and bicarbonate (HCO3-). The specific parameter that is measured can be a source of confusion.

In aqueous solution, CO2 can exist in 4 chemical forms. As a gas at room temperature, CO2 has a dissolution coefficient of 1.45 g per liter of water under 1 atm (100 kPa) pressure, so it can exist as dissolved CO2 gas. CO2(g) reacts with water to form carbonic acid, H2CO3, a weak acid with a pKa of 6.35 for the first proton, and 10.33 for the second proton. Loss of the first proton produces the monovalent bicarbonate anion, HCO3-, and loss of the second proton produces the divalent carbonate anion, CO3=. Because carbonic acid (H2CO3) is an intermediate in the carbonic anhydrase-catalyzed reaction of CO2(g) with H2O to produce bicarbonate (HCO3-) and H+, its existence in solution can be considered equivalent to the concentration of CO2(g). Since the pKa for the deprotonation of bicarbonate to produce carbonate is >10, its concentration in aqueous solution at physiological pH is negligible. Hence, virtually all CO2 in blood is either in the form of dissolved CO2(g) or bicarbonate. At physiological pH, the ratio of CO2(g) to bicarbonate is approximately 1:20.

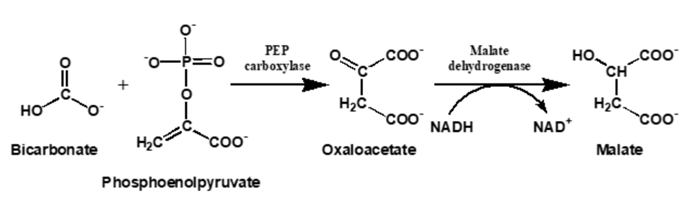

All the major automated chemistry platforms (Roche, Beckman, Abbott, Siemens, Ortho Vitros) measure total CO2 by the enzymatic reaction of bicarbonate with phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) to form oxaloacetate, followed by the malate dehydrogenase-catalyzed conversion of oxaloacetate to malate with the concomitant oxidation of NADH to NAD+, which is monitored spectrophotometrically by the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm. Because bicarbonate is in equilibrium with dissolved CO2(g), Le Chatelier’s principle requires that consumption of bicarbonate in the PEP reaction results in conversion of CO2(g) to bicarbonate to re-establish equilibrium. Therefore, these methods measure all the CO2 present, or Total CO2.

The concentration of a dissolved gas ordinarily is expressed as the pressure (or partial pressure) it exerts. CO2(g) can be measured by allowing it to diffuse across a gas-permeable membrane into an aqueous solution and monitoring the change in pH as the CO2(g) reacts with water to form bicarbonate and hydrogen ions. This does not significantly disrupt the equilibrium between CO2(g) and bicarbonate in the blood. Hence, the concentration of CO2(g) in whole blood can be measured by direct potentiometry using a flow cell, a gas-permeable membrane, and a pH electrode.

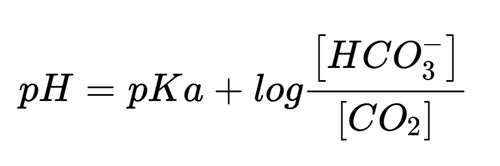

This brings us to bicarbonate: how do we measure it? Although the PEP reaction described above measures bicarbonate, it does not measure its physiological concentration because the reaction disrupts the equilibrium with CO2(g), converting the gas to bicarbonate. Direct potentiometry using a bicarbonate ion-selective electrode is one way to measure the physiological bicarbonate concentration, but interferences from hydroxide and chloride ions limit the use of these devices in clinical applications. The most common way to determine the bicarbonate concentration is to calculate it using the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation:

A blood gas instrument measures the pH and pCO2 by potentiometric methods. The CO2(g) concentration can be calculated from the pCO2 using a conversion factor of 0.03 mmol/L/mmHg, and pKa for carbonic acid, expressed as CO2(g) is 6.35, providing everything needed to solve the equation for the bicarbonate concentration. The 19th century chemist and Nobel laureate Jacobus Van’t Hoff derived the relationship between the equilibrium constant for a chemical reaction and temperature, so the calculated bicarbonate concentration will depend on the temperature at which the pH and pCO2 are measured and assumes the patient’s temperature is the same. A correction can be made if the patient is hypo- or hyperthermic, although there is debate over whether this is a necessary or advisable practice.

Additional reading

- Sanghavi SF, Albert TJ, Swenson ER. Will the real bicarbonate please stand up? Annals of the American Thoracic Society. Jul 2022;19(7):1226-1229.

- Hansen JE, Sue DY. Should blood gas measurements be corrected for the patient’s temperature? New England Journal of Medicine. Aug 7 1980;303(6):341

- Higgins C. Temperature correction of blood gas and pH measurement—an unresolved controversy. https://acutecaretesting.org (2012). Accessed 10 Sept 2025.